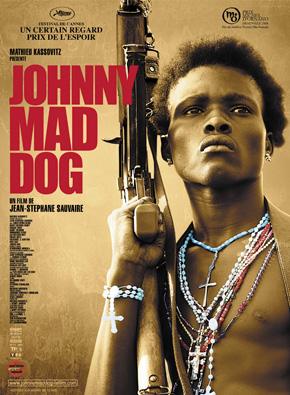

Jean-Stéphane Sauvaire, former assistant of Cyril Collard, Karim Dridi and Laetita Masson got his turn in 2003 to have his own directors’ seat. For the Images of Black Women Film Festival he proudly presents his first fictitious feature.and film Johnny Mad Dog, the winner of Best Film for Children Rights 2004.The feature is about Johnny, 15, a child-soldier, armed to the hilt, is inhabited by the mad dog he dreams of becoming. With his small commando – No Good Advice, Small Devil, Young Major – he robs, pillages, and slays everything in his path. The feature sees teenagers swamped with Hollywood imagery and disinformation playing at war with childhoods cut short we get an inside look at an Africa ravaged by absurd wars and people who are trying, in spite of it all, to survive and to save their humanity.

Does reality speak for itself in the feature?

I focused on Monrovia and the ghetto zones surrounding the city. The ex-generals pointed out war leaders who were in charge of the children at the time. I must have seen 500 or 600 children to choose 15 of them. I chose to use people’s real life stories within the film, rather that characters and actors. With them, it was approached as a therapy: not like something traumatizing, but like a game. Indeed, these were situations they had experienced but the theatre can be therapeutic.

We had to be able to film in peace, not in between three gunshots like in Medellin. Filming fiction in a place where there is shooting everywhere can be at once out of place and complicated. We needed stability. At the same time, Liberia still wore all the stigmata of war and the people wanted to speak, to testify of it: that was the most important.

What do you feel is the most important aspect of the film?

What do you feel is the most important aspect of the film?

Everything is determined by this immediacy, this importance of the present moment, this spiral in which the children are propelled. During the war, distancing themselves and reflecting is not possible for them. The system of indoctrination with the use of drugs, songs, rituals or the mechanics of a group forces us to move forward all the time.

We always loved to shoot in unlikely countries, not only for the challenge, but the authenticity of a movie is also determined by the location. Liberia was entering a period of moratorium and the President Ellen Johnson-Sirlea, who had just been elected, had undertaken the eradication of corruption and changed things in-depth. We arrived during that reconstruction period.

The AfterMath

It was unimaginable for me to reproduce the scheme the children had known during the war: the general comes, takes the children and abandons them as soon as it’s over. The year of preparation and the filming created very strong ties, a very cohesive group sentiment. I wanted to continue following the children’s progress, trying to help them in their reinsertion. These children still live day-to-day, hour after hour, with logic of survival which is hard to conciliate with a long-term project.

But it’s also from this immediacy that they have derived their strength during filming: they experienced everything in the present moment; they gave an enormous amount of themselves. I think it’s strongly present in the film and for that I thank them. Therefore, The Johnny Mad Dog Foundation was created with the aim of bringing framework and support to the young actors of the Johnny Mad Dog movie. Most of them are ex-children soldiers who have fought in Liberia with Charles or children without any family structure to assist the children in their daily life and help them develop long-term projects. To enlarge its action to the Liberian children, victims of a 14 years-long Civil War, in a country that is today in reconstruction.

I hope this film will be an opportunity to address the problem of child soldiers in the world which unfortunately, is still a topical issue and nonetheless unacceptable and intolerable.

Words by Simone Byer