Music videos are more popular than ever. Since the launch of MTV in the 1980s they’ve enabled us to connect with artists on a different level. Now there’s constant pressure for them to push the boundaries and keep the audience entertained. Some turn to dance and visual effects, but the sure-fire way to secure an audience has to be sex.

There’s nothing wrong with flaunting what you’ve got, but when it’s broadcasted around the world and shown to millions of impressionable young people, maybe someone should think about the implications of the messages they’re sending.

A Government review has blamed music videos for the early sexualisation of children. With them becoming more and more like mini-movies, is it time they were rated in the same way?

Dr Linda Papadopoulos who carried out the research has called for videos showing ‘sexual posing’ and containing ‘sexually suggestive lyrics’ not to be shown until after the 9pm watershed.

But let’s face it, if that were to happen then most of the videos out at the moment wouldn’t be allowed to air until after 9pm. So what’s all the fuss about? After all, what harm can a music video do?

Well, apparently a lot more than you might think. No doubt many of you have heard of the MTV generation, growing up watching things like YO! and The Lick.

Fast forward 20 years and things that would have been banned back then are now being shown as part of prime-time viewing. Many people like to target hip hop and rap as the main culprits, but most videos of these genres that are deemed explicit do have to wait until after a certain time to be shown – whereas pop videos like Beyoncé’s Video Phone and Rhianna’s Rude Boy don’t.

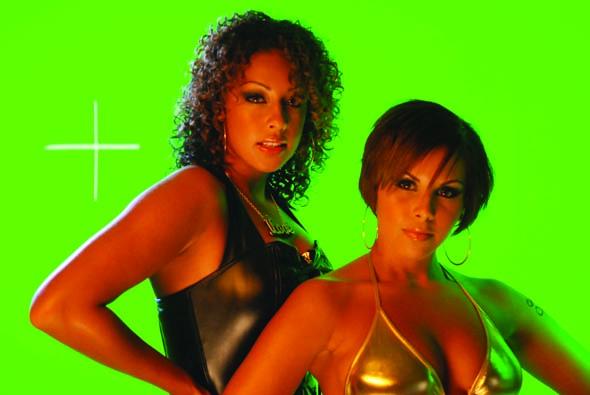

For many there’s no problem with the fact that most videos show half-naked women prancing around acting in a hyper-sexualised way. It’s the norm. But what messages do these videos send to children?

The more you see or hear something, the more it is embedded into your brain. Whether you realise it or not those things begin to form part of your belief systems and ideals. So little girls watching these videos begin to believe that they should look and behave like the pretty lady on the telly, and little boys begin to believe that women are there for their pleasure only and may even lack respect for women – after all, many songs do advocate that women are ‘bitches’ and ‘hoes’.

Surely when you’ve got four-year-olds walking around singing ‘I wanna take a ride on your disco stick’ it’s time to take the issue seriously. Some would say children are innocent, they don’t know what they’re talking about so what’s the harm? Others would think it cute. But do the consequences change when it’s a 13-year-old? Surely no one would think that’s cute.

Tom Narducci from the NSPCC calls this thinking ‘naïve’. A fair point to make when you consider, around 20 per cent of viewers for a channel like AKA are under the age of 18 during the day. These images, lyrics and values will be the things kids relate and aspire to when they grow up.

The point is music videos need to change and artists and their people need to be creative – perhaps even making more than one, or different versions, of a video for differently aged audiences. Ara from Jump Off TV thinks we will see an ‘avalanche’ of videos. He said: ‘Each track will have an official music video or two, a few live versions and maybe even a few viral spin-offs and some will be part of a movie-like story. The challenge is to supply content that the current fanbase want and would broaden the artist’s fanbase by reaching new eyes and ears.’

This self-regulatory policy sounds good. If artists were to make more than one video for a single, aiming them at different audiences, then in theory kids would be less exposed.

But what is acceptable for some might not be for others. There’s a big grey area over this issue, and until it begins to clear it is down to us to vet what young people around us are exposed to.

Should music videos receive a rating like cinematic releases? That’s for us and the powers that be to decide.

Words by Antoinette Powell